Florian Ploeckl summarizes Doug Irwin’s Ohlin Lecture, Trade Policy Disaster: Lessons from the 1930s.

International trade in summer 2012

Recently completed conferences include New Faces in International Economics at Penn State, the Midwest International Economics Group, CESifo in Munich, the European Research Workshop in International Trade at CREI, and the Rocky Mountain Empirical Trade Conference at UBC.

The agendas for the Princeton IES Summer Workshop (June 26 – 28) and the NBER Summer Institute trade session (July 9-12) are online.

European summer includes the European Trade Study Group conference in September.

Summer deadlines include July 15 for submissions to Empirical Investigations in International Trade (November) and presumably an August deadline for the October Midwest meeting.

Thanks to Bernardo Diaz de Astarloa for suggesting this post and some of its content.

What the WTO’s “Made in the World” isn’t

The WTO’s “Made in the World” initiative is a data exercise aimed at measuring and analyzing value-added trade flows.

Michele Nash-Hoff, a US manufacturing advocate, misrepresents this statistical exercise as a massive policy change. Her Huffington Post piece is curious because it accurately describes the statistical project and the shortcomings of measuring trade flows in gross terms while simultaneously quoting people out of context to invent the idea that rules of origin may soon be eliminated. (HT: Alex Raileanu)

How would you like to go shopping and find that everywhere you went, the label said “Made in the World” instead of “Made in China,” “Made in India,” “Made in USA” etc.?…

In 2011, Andreas Maurer, chief of the WTO’s International Trade Statistics Section, said “… in the past two or three years there has been huge momentum to get the necessary information” that would be used to rationalize elimination of country of origin labeling.

The World Trade Organization and the European Union moved one step closer to eliminating “country of origin” labeling. On April 16, 2012, the European Commission and WTO held a conference to mark the launch of the World Input-Output Database (WIOD). This new database allows trade analysts to have a better view of the global value chains created by world trade…

Director-General Pascal Lamy has said that “improved measurement and knowledge of actual trade flows will help better understand the interdependencies of today’s national economies, supporting the design of better policies and better trade regulation worldwide.”…

This Initiative could have dire consequences for America’s manufacturers and consumers. For manufacturers, it could eliminate one of the options allowed by the WTO — filing a charge for product “dumping” against another country to have countervailing duties applied against that country. For consumers, “Made in the World” labels wouldn’t allow you to protect your family from the tainted, harmful, and even life threatening products coming from China.

I’m interested in these data initiatives and I have never ever seen such a policy implication suggested. It’s clearly absurd.

If the label said “Made in the World”, one couldn’t know if the product were domestic or foreign, so no trade duties of any sort could apply. Is this what we imagine WTO member countries are headed towards? Eliminating rules of origin would render every preferential trade agreement and preference scheme obsolete by implementing perfectly non-discriminatory trade. The world has never been close to such a policy regime. I’m bemused that Ms Nash-Hoff has managed to turn an exercise in data collection and analysis into a scary free-trade conspiracy.

The WTO’s Andreas Maurer posted in the comments section of the Huffington Post to set the record straight:

Your article refers to another article which stated that “… in the past two or three years there has been huge momentum to get the necessary information” that would be used to rationalize elimination of country of origin labeling. This is not true.

That article by Mr Richard McCormack referred to the WTO’s Public Forum Session in September 2011. But that Session in no way propagated the “elimination of country of origin labelling” and the introduction of a “Made in the World” label. Rather it stated that current international trade statistics do not adequately reflect where value added is created.

Understanding where value is created is very important for business and national policy makers alike, and is the object of intense academic investigation. As your article points out, a research consortium produced a public database last month. In addition, WTO and OECD are jointly working to develop statistics on trade in value added.

But this research project does not affect whatsoever the way country of origin is reported by official statistics collected through customs. There is no intention at all to have the “Made in the World” logo actually appearing on any traded product. This logo only illustrated a statistical concept. Thus the article above misrepresents the objectives of the WTO.

How big are the gains from trade?

One of the most-mentioned trade papers of the last couple years is “New Trade Models, Same Old Gains?” by Arkolakis, Costinot & Rodriguez-Clare, now published in the AER. Their theoretical work shows that, for a broad class of theoretical models that includes the Armington, Eaton and Kortum (2002), and Melitz-Chaney approaches, the gains from trade are characterized by a formula involving only two numbers – the domestic expenditure share and the trade elasticity. The former can be straightforwardly obtained from the data. The latter needs to be estimated, which is more involved but feasible. ACR shows that their formula says that US welfare is about 1% higher than it would be under autarky.

In the words of Ralph Ossa, “either the gains from trade are small for most countries or the workhorse models of trade fail to adequately capture those gains.” Different people come down on different sides of that choice. Ed Prescott, for example, is clearly in the latter camp.

Ossa has a new paper, “Why Trade Matters After All“, aimed at reconciling this divide:

I show that accounting for cross-industry variation in trade elasticities greatly magnifies the estimated gains from trade. The main idea is as simple as it is general: While imports in the average industry do not matter too much, imports in some industries are critical to the functioning of the economy, so that a complete shutdown of international trade is very costly overall…

I develop a multi-industry Armington (1969) model of international trade featuring nontraded goods and intermediate goods and show what it implies for the measurement of the gains from trade…

Loosely speaking, the exponent of the aggregate formula is therefore the inverse of the average of the trade elasticities whereas the exponent of the industry-level formula is the average of the inverse of the trade elasticities which is different as long as the elasticities vary across industries.

allowing for cross-industry heterogeneity in the trade elasticities substantially increases the estimated gains from trade for all countries in the sample. For example, the estimated gains from trade of the US increase from 6.4 percent to 42.0 percent if I do not adjust for nontraded goods and intermediate goods and from 3.8 percent to 23.5 percent if I do…

the 10 percent most important industries account for more than 80 percent of the log gains from trade on average.

Thinking about the firm-size distribution

[Note: This post isn’t about international economics. I’ll use an example from trade to comment on a feature of the US real-estate market.]

In a letter to the Economist, the president of the National Association of Realtors writes:

[I]t is not true that large brokers dominate the industry. In fact, the real-estate industry consists mostly of independent contractors and small firms. Eight out of ten realtors work as independent contractors for their firms.

The second sentence appears to be a non-sequitur, unless one thinks that existence is informative about dominance. It’s not. In their first glance, antitrust authorities would look at concentration ratios or Herfindahl–Hirschman indices, because dominance is about economic outcomes, such as market shares, not mere existence.

According to Bernard, Jensen, Redding, and Schott’s JEP survey, four percent of the 5.5 million US firms export. That makes 220,000 exporters. The top ten percent, just 22,000 exporters, are responsible for 96% of US exports. Would we say that “larger exporters do not dominate exporting because the exporting set of firms consists mostly of small exporters”? Of course not.

When thinking about the sales distribution, we care about the exponent of the power law characterizing it, not merely the fact that its support includes small sizes.

Quick links

My blogging has taken a back seat to my research recently. Here are some quick links that I wish I had more time to discuss:

- Gary Hufbauer & Jeff Schott: Will the WTO enjoy a bright future? (pdf)

- Simon Lester on how Andrew Rose measured trade protection

- Timothy Taylor summarizing Hufbauer and Sean Lowry on US tire tariffs: $900,000 per job saved.

- Imports Work for America Week is an initiative by a coalition of organizations representing tens of thousands of businesses employing millions of American workers across the United States who depend on access to imports to compete globally. [HT: Scott Lincicome]

Melitz & Trefler – Gains from Trade when Firms Matter (JEP 2012)

The Spring 2012 JEP has a symposium on international trade. I already mentioned the great article on the Ricardian model by Eaton and Kortum. Another very nice contribution to the symposium is a piece by Marc Melitz and Daniel Trefler on the “Gains from Trade when Firms Matter” (pdf).

Today, we focus on three sources of gains from trade: 1) love- of-variety gains associated with intra-industry trade; 2) allocative efficiency gains associated with shifting labor and capital out of small, less-productive firms and into large, more-productive firms; and 3) productive efficiency gains associated with trade-induced innovation.

This survey distills a very large body of literature. It belongs on your syllabi.

Rose: Protectionism is acyclical

Almost everyone agrees that protectionism is countercyclical; tariffs, quotas, and the like grow during recessions. The abstract of Bagwell and Staiger (2003) begins “Empirical studies have repeatedly documented the countercyclical nature of trade barriers”; for support, they provide citations of eight papers which “all conclude that the average level of protection tends to rise in recessions and fall in booms.” Meanwhile, Costinot (2009) states: “One very robust finding of the empirical literature on trade protection is the positive impact of unemployment on the level of trade barriers. The same pattern can be observed across industries, among countries, and over time.” …

The sample is split into two in the scatter-plots to the right. Above, the data show a positive relationship between 1906 and 1942; high unemployment in the 1930s tends to coincide with high tariffs. This relationship is strikingly reversed in the graph below, which scatters tariffs against unemployment for the period between 1946 and 1982. Since World War Two, high American unemployment seems to coincide with low American tariffs; protectionism seems to be, if anything, cyclical…

The goal of my recent work has been to show that, at least since World War II, protectionism has not been countercyclic. While this runs counter to conventional wisdom, the evidence is reasonably strong; no obvious measure of protectionism seems to be consistently or strongly countercyclic.

An interesting question occurs: why is protectionism no longer countercyclic? Before World War I (and in contrast to more recent times), tariffs contributed greatly to the national treasury, there was no GATT, and the Gold Standard ruled. But it turns out that protectionist policies of countries with large and small budget deficits seem to react similarly to business cycles, as do those of countries inside and outside the GATT/WTO, those with fixed and floating exchange rates, small and large countries, and open and closed countries. If there has been a shift in the cyclicality of protectionism since WWII, it’s hard to be sure why.

Perhaps, just perhaps, the switch in the cyclicality of protectionism – if there has indeed been one – is a triumph of modern economics. After all, there is considerable and strong consensus among economists that protectionism is generally bad for welfare. And there is no doubt that economists are aware and actively involved in combating countercyclic protectionism; this was especially visible during the Great Recession, which saw the successful launch of Global Trade Alert in June 2009. If – and it’s a big if – the efforts of the economic profession are part of the reason that protectionism is no longer countercyclic, then the profession deserves a collective pat on the back. But in that case the profession should also consider setting its sights higher. If economists have helped reduce the cyclicality of protectionism, then perhaps they should focus on actually reducing protectionism.

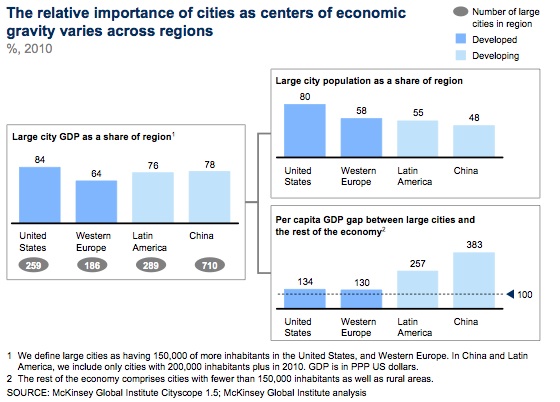

Cross-country comparisons of large cities

A number of people have highlighted a new McKinsey Global Institute report on US cities in the global economy.

Here’s the MGI summary:

In a world of rising urbanization, the degree of economic vigor that the economy of the United States derives from its cities is unmatched by any other region of the globe. Large US cities, defined here as those with 150,000 or more inhabitants, generated almost 85 percent of the country’s GDP in 2010, compared with 78 percent for large cities in China and just under 65 percent for those in Western Europe during the same period. In the next 15 years, the 259 large US cities are expected to generate more than 10 percent of global GDP growth—a share bigger than that of all such cities in other developed countries combined.

I find this definition of a “large city” to be puzzling. I’ve searched the report for the word “150,000” and the authors don’t seem to have provided an explanation for this measurement choice. That’s unfortunate, because using this cutoff for cross-country comparisons has big implications that may lead readers astray. But before we get into those measurement details, let’s just make clear what the report’s executive summary does and doesn’t say.

At Ezra Klein’s place, Brad Plumer says:

The report’s authors argue that the city gap between the United States and Europe account for about three-quarters of the difference in per capita GDP between the two. In other words, the United States appears to be wealthier than Europe because it has a greater share of its population living in large, productive cities.

That second sentence isn’t plausible. Look at Exhibit 1 in the McKinsey report, which I’ve reproduced here:

The gap in per capita GDP between the US and Europe is about 35%, according to the MGI figures in Exhibit 2. The “large city” premia in the United States and Europe of 34% and 30% are virtually the same. That means that the difference in per capita income attributable to the difference in “large city” population shares is the large city premium (~30pp) times the difference in large city population shares (22pp). The six to seven percentage points explained by this difference in population shares is at best one-fifth of the 35% gap between US and EU incomes. You can confirm this quick calculation by studying the decomposition in MGI’s Exhibit 2. Moving more people into large cities wouldn’t meaningfully reduce the US-EU per capita income gap.

Over at Atlantic Cities, Nate Berg summarizes Exhibit 1 as “though cities all over the world are responsible for major contributions to the global gross domestic product, the concentration of large – and especially semi-large – cities in the U.S. outperforms them all.” He quickly notes that “the sheer number of large cities in the U.S. is clearly a major part of the difference, especially with about 80 percent of the country’s population concentrated in these metropolitan regions.” In fact, it’s more than a major part of the difference – it’s basically all of it.

“Large city” economic output is a larger share of total economic output in the United States because “large city” population is a larger share of population in the United States. US “large cities” have 80% of the US population and produce 84% of US output. European “large cities” have 58% of their population and produce 64% of their output. If “large cities” are more important to GDP in the United States (or in Plumer’s interpretation the US “derives more economic benefit from its cities than any other country on the planet”), it’s because a larger fraction of the population lives there.

This is a statistical artifact created by using the same population cutoff to define “large cities” in countries with quite different national populations. It’s not clear that telling us that a greater share of Americans live in metropolitan areas with populations greater than 150,000 than Europeans tell us that these economies operate differently.

The typical country’s city size distribution is decently characterized by a power law, Zipf’s law, which implies a log-linear relationship between a city’s size and its rank in the size distribution. Zipf’s law doesn’t hold for the entire distribution, but we know from Rozenfeld, Rybski, Gabaix & Makse (AER 2011) that it’s a decent approximation for places with more than 10,000 or so people in both the US and UK.

I’ve displayed the city size distributions for both the US and UK in the figure below. The US distribution stops around 10.8 because only 280 (consolidated) metropolitan areas were defined in 2000. Rozenfeld et al have shown that it’s safely to linearly extrapolate down to something like 9.4.

Given the UK population, increasing the fraction of UK residents who live in “large cities” with populations greater than 150,000 would require the emptying out of smaller metropolitan areas. While such migration is entirely possible, it would violate the expected city size distribution. We don’t see such top-heavy city size distributions in economies with a decent number of cities (of course, city-states like Singapore violate Zipf’s law). If you know the populations of New York and London and are familiar with Zipf’s law, then it’s not at all surprising that a greater fraction of the US population is found in metropolitan areas above some common population threshold. I don’t think that tells us much about the economic mechanisms determining the role of US cities in the global economy.

Addendum: The MGI report compares Western Europe to the United States, but Zipf’s law holds at the country level. Using Western Europe, which has an aggregate population akin to that of the US, doesn’t give us reason to expect a similar share of the population to live in cities with populations exceeding 150,000. There is no Western European city the size of Los Angeles or New York. [Thanks to @ptitseb for suggesting this clarification.]

Moretti – “The New Geography of Jobs”

Enrico Moretti has written a book that’ll be released in about a month. It’s titled The New Geography of Jobs.